Research Overview

Overview

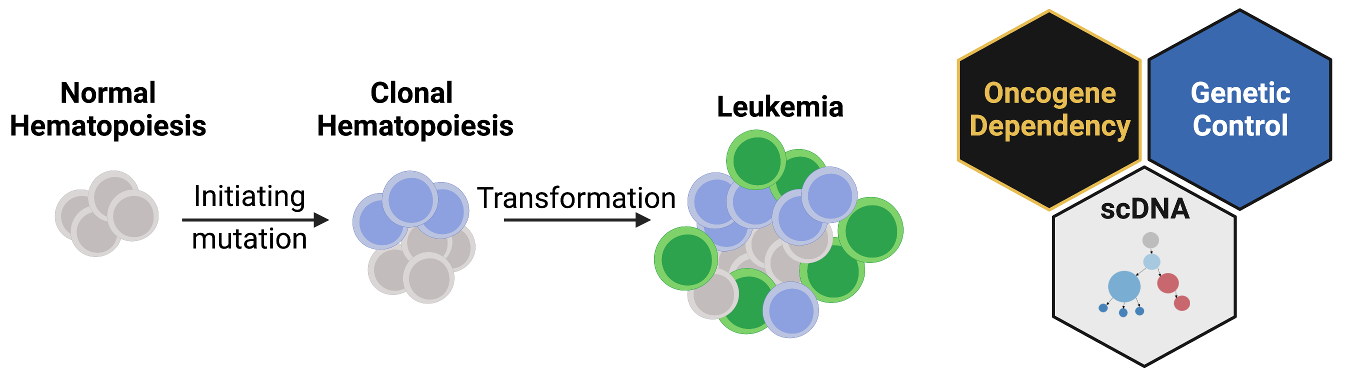

I am an incoming Assistant Professor in the Department of Cancer Biology at the University of Pennsylvania. The lab will open on September 1st 2022. I completed my postdoctoral training with Dr. Ross Levine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center where I studied how acquired mutations can cause normal blood and immune cell production to go awry. As people age, many will acquire mutations in their blood, a state termed clonal hematopoiesis. Despite relatively normal blood production, clonal hematopoiesis has been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and development of leukemia. Estimates of the prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis vary by detection method and age group, with some estimates of 25-50% of individuals over the age of 80 being affected. Despite this widespread phenomenon only a fraction of these patients will go on to form leukemia. I am particularly interested in this latter “transformation” event where I study the following broad questions:

- What are the necessary steps for a mutant cell to transform to leukemia?

- After transformation, how do these leukemic cells affect normal non-mutated cells?

- How can we revert or halt transformed cells early in disease development to prevent disease development?

Approach

To address these questions, I use a combination of wet laboratory techniques and computational genomic approaches. Specifically, I develop mouse models of disease where I can recreate the genetic events that can take up to 60+ years to develop in patients. In mice, I can engineer multiple mutations that can be activated by distinct chemical inducers. This genetic toolkit combines Cre, Dre and Flp recombinases as well as CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering offering precision genetic control in modeling disease development. These tools can be used to model different orders/combinations of mutations, functionally testing clonal evolution patterns observed in patients. Furthermore, we can combine multiple recombinases where one acts as an on-switch for a mutation, and another recombinase can turn the mutation off. This toggle let’s us determine when a mutation is necessary for a disease and represent a strong therapeutic target for future development.

If the mouse models above are the functional machine of discovery, genomic profiling of patient samples is the fuel. The advent of affordable next generation sequencing approaches resulted in an explosion of data, where we now have a near complete catalog of mutations that are associated with leukemia. However, these sequencing efforts leave several questions unanswered:

- Which mutations occur in the same cell?

- Is leukemic disease one monolithic group of cells, or a collection of many different mutant cells?

- Are specific mutations associated with different cell types?

To address these questions, we have utilized single cell DNA sequencing (scDNA) to increase the resolution from a single patient sample to thousands of individual cells in that patients leukemia. In each of these cells we can assess which mutations are present, as well as which proteins are expressed on the surface of the indicating where this cell lays in the blood developmental cascade (from stem cell to differentiated immune effector cells). This powerful technology can be used to discover patterns of co-mutation synergy, and how specific mutations combine with specific cell types to lead to disease expansion.